|

|

|||||||||||

|

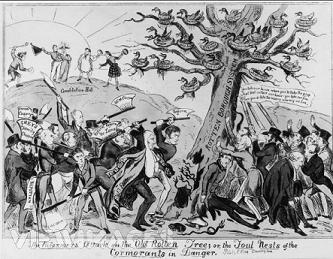

In the history of democratic reform from King John and the Magna Carta onwards, those in power have always resisted surrendering some of that power to others who might also claim a right to the decision making process. Rotten Boroughs For at least one hundred years up until the Reform Act of 1832 the UK had a quirk in the electoral system known as Rotten Boroughs, a.k.a. pocket boroughs. Parliamentary constituencies were divided up into a kind of town and country affair where both the centres of population, the towns, and also the counties sent representatives to parliament. Even though all of the approximate 46 counties sent two so called ‘knights of the shire’ to Westminster, the towns, referred to as boroughs, were represented in a far less equitable manner. Specifically chosen boroughs were originally given a Royal Charter by the monarch to be allowed to be represented. These grants were due to the contemporary prosperity of the town or simply for the monarch to install another supporter in parliament. The issuance of charters was never reviewed and due to demographic changes over time, the population of boroughs varied significantly. This together with the fact that the franchise at the time was restricted to only protestant, land owning, males meant that representation was very disproportionate. Although by 1831 the average number of voters in an electorate was 715, fifty boroughs had less than 50 voters each, including Bramber in West Sussex with 20 voters and both Old Sarum in Wiltshire and Gatton in Surrey with a grand sum of seven voters each. In effect that meant that a quarter of the population could have as many representatives in Parliament as the remaining three quarters. Also bear in mind that voting was not secret, and thus it was very easy for people of influence to ensure how some seats would vote. An episode in the Blackadder television comedy series set in Regency England had Blackadder as the sole voter for a midlands constituency installing his lackey Baldrick as the new member of parliament.

Twentieth CenturyFrom the Reform Act of 1832 to the early decades of the twentieth century countries that were democracies had mostly surrendered to the concept of universal suffrage. That is: any adult citizen had the vote, immaterial of rank, wealth, gender, religion, race or national origin. However for some people elected to public office, being in government had the same allure that historically many people in positions of power experience: not only to use your position to feather your own nest and or those of your supporters, but also to impose your beliefs and values on the population in general. If the universal franchise means that you can no longer deny the vote to those who would probably vote against you engaging in such actions, then there still may be avenues open to you to facilitate your intentions. You may be forced to give everyone the vote, but fortunately for you (and unfortunately for the public) there would often be nothing to prevent you giving your supporters and fellow travellers more than one vote. One Person One Value, NotAlthough technically not giving anyone more than one vote at the polling booth, all the astute politician has to do is to ensure that the electorates of his supporters only need be small in population while those of his opponents comprise large population groups. Thereby 100,000 of your supporters in two 50,000 size electorates could send two representatives to parliament to be opposed by just one parliamentarian representing 100,000 of your opponents of one 100,000 size electorate. Malapportionment is the practice, existing well into the twentieth century, in so called ‘liberal democracies’ where electoral districts, even though still sending the same number of representatives to parliament/congress, comprise quite different numbers of voters. Australia“All states other than Tasmania have, at some stage, utilised electoral zones that have been allocated different enrolment quotas so that seats in one part of the state contained fewer voters than those in other parts…”1 Malapportionment was more prevalent in the rural states of Western Australia, Queensland and South Australia where the excuse was that large sparsely populated areas were too much for just one representative to adequately cover. By 1968 in South Australia it reached surprising proportions whereby the average rural electorate had only a third of the population of the average metropolitan electorate. The most extreme example was where the largest city electorate sent the same number of MPs to State Parliament as seven rural electorates.2 United StatesThe Supreme Court case of Reynolds v Sims 377 U.S. 533(1964) ruled that districts of state legislatures had to be approximately equal in population.3 Until that time numerous states had engaged in varying degrees of malapportionment that would even make the Electoral Commissions of South Australia blush. Some Examples:4

Modern DayIn the twenty-first century the principle of one person one value still has not been fully endorsed in either Australia or the UK.

1. Parkin, Summers and Woodward, Government, Politics, Power and Policy in Australia, Longman, Melbourne, 1996, p192.

|

| [Home] [Glossary] [Chartists] [Malapportion] [Voting] [Info] [About Us] [Demcy. Index] |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||